ARTICLE

Development and validation of the Iranian version of the Patient Privacy and Confidentiality Scale

Fatemeh Movafegh, Abbas Abbaszadeh, Maryam Rassouli, Mohammad Sajjad Lotfi, Malihe Nasiri, Samira Mokhlesi

Published online first on October 5, 2020. DOI:https://doi.org/10.20529/IJME.2020.102Abstract

The aim of this study was to develop and psychometrically validate the Iranian scale of patient privacy and confidentiality. This methodological study was conducted in two stages: first, a conventional content analysis was used to qualitatively identify concepts of privacy and confidentiality. Then, the face validity, content validity, and construct validity were assessed. Internal consistency coefficient and total consistency were checked. KMO and Bartlett’s test were used to examine thequestionnaire for factor analysis. EFA identified seven factors that accounted for 55.25% of the total variance in the questionnaire score. The total Cronbach’s α coefficient was 0.84 for the whole instrument. The Spearman reliability coefficient of the instrument was 0.91 using the test–retest method.The final Iranian version of the Patient Privacy and Confidentiality Scale can be used as a valid and reliable instrument to measure the rate of observation of patient privacy and confidentiality.Keywords: privacy, confidentiality, secrecy, scale

Introduction

Valuing human dignity is one of the most important components of human rights in healthcare systems (1). Human dignity is an extensive multifaceted concept, the major aspects of which have attracted the attention of researchers (2). Patient privacy and confidentiality, defined as “any individual’s feeling towards their nature, position, independence, and private space”, is considered one of the most fundamental dimensions of patient dignity and is a human right (3, 4). Developed countries have passed a number of acts and legislations to support and protect this right (5). Moreover, the World Health Organization (WHO) has clarified this concept in medical ethics and patient rights declarations to aid in theobservance of patient privacy in therapeutic settings (6). Attendance of individuals in clinical setting gives them a greater inclination to protect and control their privacy, regardless of their position or health status (7). This is a duty of various members of the treatment team (4). Given that nurses are responsible round-the-clock for patient care, they play a greater role in observing patient privacy and confidentiality (4). Observing patient privacy is one of the most basic concepts of ethical care (2, 3), so it is the key guiding principle of the ethical code of nursing (8). On the basis of this code, the foremost professional responsibility for nurses is caring for patients’ needs and providing an atmosphere that respects human values, beliefs, rights, and dignity (8). Observing patient privacy results in some consequences for the individual and the healthcare system (4). On the other hand, overlooking it has been found to lead to loss of patient confidence in the treatment team, predisposing them to a reduced quality of care, prolonged hospital stay, delayed recovery, and increased costs (4, 9). Despite the importance of patient privacy, few studies in Iran have focused on the issue (10). The study by Dehghani et al indicates that nurses have little awareness of patient privacy and dignity and that their perception of the concept is different from that of patients (11). Tehrani et al mention in their study that despite the importance given to privacy by nurses, from the patients’ perspective, the observation of patient privacy and patients’ satisfaction in this area were very low (6). The results of the study by Hajbaghery et al of 330 elderly patients hospitalised in Isfahan and Kashan demonstrate that patient privacy was well observed only in 16.4% of cases (12). The low number of studies in this field may be attributed to the absence of a valid and reliable inventory for measuring the observation of privacy (10). Özturk et al believe that there is no valid and reliable instrument available for examining the observation of patient privacy and confidentiality (13). Evaluating patient perspectives can allow for some modifications in the methods of service provision on the basis of standard health models. Presently, the patient-centric approach focuses on continual feedback from patients and the steady improvement of processes and organisational care provisions (8).

Although a few inventories like the Privacy Attitude Questionnaire (RAQ) (14), Privacy Observation and Patient Satisfaction Scale (7), Observation of Pediatric Privacy in Pediatric Wards (15), Scale of Professional Ethics Observation from Nurses’ and Patients’ Perspectives (16), and the Privacy Model (17) have been published, they suffer from limitations.The Privacy Attitude Questionnaire (RAQ) only checks the informational dimension and the protection of electronic documents. The scale developed by Dehghani et al checks all the dimensions of privacy but physical privacy is emphasised more than others (16). Foroozadeh et al used a scale that only deals with children’s information and physical privacy, and adult considerations for privacy are not used (15). The limitations of these instruments, such as cultural dependence and bias, a focus on a specific population, lack of attention to the various aspects of privacy, and the lack of comprehensiveness have led to their limited utility.Given the importance of patient privacy and confidentiality, their role in promoting quality care and health services, and the lack of a suitable scale for measuring the observation of patient privacy, this study developed and psychometrically validated the Iranian version of the Patient Privacy and Confidentiality Observation Scale.

Subjects and methods

MethodologyThis methodological study was carried out in two stages during the period 2017–2019 in Tehran.

Item generationThe literature review was conducted using the keywords “privacy”, “confidentiality”, and“secrecy” and other related English and Persian terms, which were entered on PubMed, Ovid, Scopus, Science Direct, SID, Google Scholar, and Thomson Reuters. The inclusion criteria were Persian or English sources, the presence of keywords in the study, and the publication of studies in prestigious domestic or foreign journals during 2010–2019.

The initial search revealed 174 records. In the first stage, repeated articles were excluded from the results. Finally, those articles that met the inclusion criteria were selected for investigation. Sixty studies (40 Persian and 20 English) were examined at this stage. The pool of 93 items was designed on the basis of findings and codes extracted from the literature review. Then, 32 items were removed due to conceptual similarities by a board of experts (an instrument developer, a bioethical specialist, a psychiatric nurse, two nursing ethics specialists, and a nurse). They selected 64 of the 93 items for the first draft of the instrument. In this way, the initial questionnaire for assessing psychometric properties was prepared based on a 5-point Likert scale (completely agree=5, agree=4, indifferent=3, disagree=2, completely disagree=1).

ValidityFace validity and content validity

To investigate content validity qualitatively, 10 experts familiar with privacy and pertinent concepts (bioethics, nursing ethics, instrument development, and psychiatric nursing) were asked to evaluate the questionnaire in terms of grammar, wording, item allocation (qualitative content validity) and to add more suitable items to the pool. To examine content validity quantitatively, the experts were asked to investigate estimate the content validity ratio (CVR) and content validity index (CVI). To assess the CVR, they were asked to score the necessity of each item on a 3-point Likert scale ranging from necessary=1 to unnecessary=3. After calculating the CVR of each item, the inclusion or exclusion of the item was determined on the basis of critical points assigned according to the Lawshe table. Items with CVR<0.62 (critical point in the Lawshe table for 10 experts) were excluded and the rest maintained. The experts were asked to investigate the relevance of the items by assessingthe CVI on a 4-point Likert scale. The CVI of the whole instrument was examined using a Kappa designating agreement on relevance.Further, to investigate the face validity from the target group’s perspective, the questionnaire was read out separately to 15 patients by the first researcher, who was familiar with the items and concepts in them. Fifteen patients hospitalised in Tehran hospitals (Shohadaye Tajrish Hospital, Imam Hussein Hospital, and Loqman Hospital) were selected using a convenience sampling method. Patients’ perceptions of the items were explored. The items that were difficult to understand or ambiguous were revised based on patients’feedback.

Construct validityConstruct validity was investigated with exploratory factor analysis (EFA). For EFA, 3–10 samples are required per item in the questionnaire (18). In this questionnaire, 4 samples were selected for each item (46 items), so the sample volume was set at 200 after considering subject attrition. Thus, 200 patients hospitalised in internal medicine, neurology, ER, and orthopaedic wards of hospitals in Tehran (Shohadaye Tajrish Hospital, Imam Hussein Hospital, and Loqman Hospital) were selected using a convenience sampling method. They began participating in the study after signing the informed written consent form. These were the inclusion criteria: aware of the environment, no history of mental disorders, ability to communicate, lack of emergency situation, the passage of at least 48 hours since hospitalisation, aged above 18 years, literate and having signed the informed written consent. The exclusion criteria were incomplete questionnaire and interference of attendants while completing the questionnaire. By referring to Tehran hospitals (Shohadaye Tajrish Hospital, Imam Hussein Hospital, and Loqman Hospital), the researcher talked to patients, and explained the study objectives to them. If they agreed and met the inclusion criteria, the scale was provided to them. The questionnaires were then collected from the hospitals and, after ensuring the accuracy of completion, were prepared for analysis.

KMO (Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin) and Bartlett’s test were used to determine the sampling sufficiency and investigate the correlation coefficient matrix among the items. To extract the number of factors, the least factor loading of 0.35 and Eigen value>1 were used. Varimax rotation was used to facilitate interpretability.

ReliabilityThe internal consistency coefficient was estimated with Cronbach’s α. Test–retest was used to establish the reliability coefficient of the instrument. Since the questionnaires were anonymous, patients were asked to voluntarily write their file number on the questionnaires. Then, 30 questionnaires were selected from among those with file numbers. Test–retest was administered within two weeks and the consistency of the instrument was established using an intraclass correlation coefficient. If a patient was discharged or did not complete the questionnaire for any reason, another questionnaire with a file number on it was substituted for the incomplete one. The data were gleaned via self-reported. When administering the questionnaires, the researcher first explained the research topic, goals, and procedures to the patient in a private examination room. After obtaining their informed consent, the questionnaire was given to the patient to be completed after the researcher left the room. When they were done, the patient put it in the questionnaires box.

Ethical considerations

Approval of the research proposal was conferred by the Committee of Ethics in Human Research at Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences under the code IR.SBMU.PHARMACY.REC.1397.183 in 2018. The patients were assured of anonymity and confidentiality and that they could leave the study at any stage without consequences.

Data analysis

The data were analysed with SPSS 16 using descriptive statistics. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to examine the normal distribution of data. The Spearman correlation coefficient was used to measure the correlation between the scores of the two tests. Cronbach’s α coefficient and ICC were used to investigate reliability. Given the abnormal distribution of data, principal axis factoring (PAF) along with Varimax rotation were used to extract items in the Iranian Patient Privacy and Confidentiality Scale by considering a least factor loading of 0.35 (p=0.05).

Results

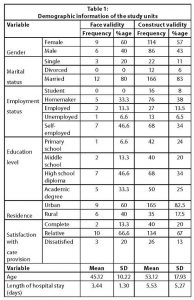

Face and content validityTo establish qualitative content validity, expert opinions were used to modify and revise the wording and grammar of most of the items to simplify them and make them objective. For instance, the item “How far do ward staff provide suitable conditions for your prayer and worship?” was converted to “Treatment staff provides the required facilities for my prayers and worship”. Similarly, the item “Access to phone or paging attendant if necessary” was changed to “The treatment staff helps me to access a phone or page my attendant if required”. The CVR ranged between 0.6 and 0.8 for each item. The 12 items with CVR<0.62 were omitted. CVI was estimated to be between 0.3 and 1 for individual items in relation to relevance, leading to the omission of 6 more items. CVI was estimated at 0.89 for the whole instrument using Kappa designating agreement on relevance. During the content validation stage, 18 items were eliminated and 46 items maintained. The demographics of the samples in the construct validation phase and other information are displayed in Table 1. This shows that 57% of the participants were female. The mean age of patients was 53.12±17.93 years, with a mean hospitalisation time of 5.53±5.72 days.

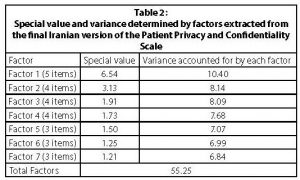

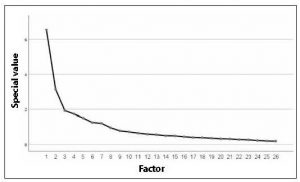

Construct validityDuring this stage, 46 items were added to the model; of these, considering 0.4 as the minimum factor load, 20 items were deleted, with 26 items left. KMO and Bartlett’s test were used to examine the capability of the questionnaire for factor analysis. KMO indicated the sufficiency of the sample volume (0.82). Bartlett’s test demonstrated that the correlation matrix among the questionnaire items is fit for analysis (X2=2212.53, p<0.001). Factor analysis resulted in 7 factors that accounted for 55.25% of the total variance in the score of the scale developed in this study (Tables 2 and 3; Figure 1).

Figure 1: The screen plot of the Iranian version of the Patient Privacy and Confidentiality Scale

Internal consistency and instrument reliability

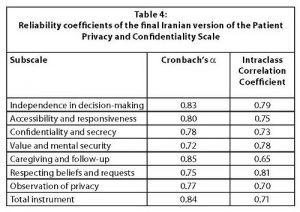

Internal consistency was estimated for each item using Cronbach’s α coefficient >0.72, and the reliability coefficient of the whole instrument was 0.84. Regarding instrument consistency, the test–retest reliability coefficient was 0.91 using the Spearman correlation coefficient (p<0.0001, ICC=0.71, p<0.0001) (Table 4).

Scoring procedureThe final scale consisted of 26 questions in 7 domains, based on a 5-point Likert scale (completely agree to completely disagree). The score range of the scale, based on the above explanations, is 26–130, with higher scores indicating a greater level of privacy. We can use the following formula and determine the cut-off score of the scale.

Cut-off in Likert scale= (maximum total score + number of questions)/2

A score of more than 78 shows an adequate level of privacy.

Discussion

This study developed and psychometrically validated the Iranian version of the Patient Privacy and Confidentiality Scale. To determine the validity of the scale, 64 items were identified based on codes. The outcome of a face validity and content validity assessment was a 46-item questionnaire. The results of construct validity yielded an instrument with 26 items in seven domains, including independence in decision-making, accessibility and responsiveness, confidentiality and secrecy, valuing mental security, caregiving and follow-up, respecting beliefs and requests, and observation of privacy and confidentiality. These seven factors constituted 55.25% of the total variance of the questionnaire.

In the first stage, the content validity of the instrument was assessed by experts before the questionnaire was answered by participants in the target group. The content was modified and clarified wherever necessary. Items with CVR>0.62, were omitted, on the basis of 10 experts’ opinions. Then, 12 items with CVR less than the expected value in the Lawshe table were eliminated and 52 items retained for the following stages. Thus, it can be said that all items in the instrument were necessary. The CVI for relevance of each item fell between 0.8 and 1 and the total CVI was >0.9. Six items with CVI<0.70 were omitted and 46 items maintained for subsequent analysis. Items with CVI<0.70 were not acceptable and were revised or omitted. Regarding CVI of the whole instrument, values >0.86 were acceptable (19, 20). By this measure, the Iranian Patient Privacy and Confidentiality Scale possesses acceptable content validity.

In interviews, 15 patients were asked to evaluate the questions regarding their level of difficulty, irrelevance, and ambiguity (qualitative face validity). The changes made in this version following the process of qualitative face validity have been more than cosmetic. These changes have created a better and simpler understanding for the target group and are in accordance with the culture and circumstances of that group (22). The content validation of the developed scale based on expert opinions was mostly concerned with simplicity, clarity, perceptibility, and intelligibility in the wording of the items. At this stage, most items were revised and reworded to make them more comprehensible to patients. The rate of variance determined by extracted factors during EFA is one of the most important parameters used in judging the construct validity of an instrument; thus, Polit et al state that the factors identified in the factor analysis should account for at least 60% of the total variance in scores, and each identified factor should account for at least 5% of the total variance in scores (19). Furthermore, many sources assert that the identified factors should account for at least 50% of the total variance in scores (23, 24, 25). The EFA suggested that the final version of the scale developed in this study is a 7-factor instrument that has construct validity. The following factors were identified through the developed questionnaire: in ethical patient care, the patient enjoys independence in decision-making (26, 27, 28), the patient’s caregivers are accessible and responsive (29), confidentiality and privacy are observed in patient care, the patient feels valued and secure (30, 31), the patient is cared for and followed-up on (32), their beliefs are respected (33), and their privacy and confidentiality are respected (34, 35).

Özturk et al provided the Patient Privacy in Nursing Scale, some aspects of which resemble those designed in the present study (privacy, secrecy, confidentiality, and respect for beliefs and requests) and account for >61% of the total variance. Also, the aspects of physical privacy (9), dynamism of privacy, bodily privacy, spiritual and religious privacy (6), and respect for beliefs, secrecy, and confidentiality (36) were similar to those in the Iranian version of the Patient Privacy and Confidentiality Scale. Cronbach’s α for the whole instrument was 0.84. Ebadi et al believe that an acceptable and reliable α ranges between 0.7 and 0.9. An instrument with α<0.7 is not reliable and α>0.9 indicates confounded items, so similar items need to be deleted. Hence, the scale developed in this study enjoys suitable reliability (21). The α coefficient was 0.93 for Özturk et al’s questionnaire, 0.81 for the Privacy Observation Scale, 0.88 for the Privacy Observation and Patient Satisfaction Scale, and 0.89 for the Nurses’ Privacy Observation from Elderly Perspective Scale.

The Spearman test–retest consistency coefficient of the instrument was 0.91. Daly et.al (2014) renders a correlation coefficient >0.7 as acceptable (37). The correlation coefficient between scores of the test and retest examines the consistency and repeatability of a test (21, 38). Given the correlation coefficients obtained in this study, it may be asserted that the instrument enjoys appropriate consistency and repeatability and is, therefore, suitably reliable. The ICC of the whole instrument and its factors was >0.7. In interpreting this, ICC<0.5 is weak, ICC between 0.50 and 0.75 is moderate, ICC between 0.75 and 0.90 is good, and ICC>0.90 is excellent (39). The ICC of the scale developed here was between 0.47 and 0.71, with acceptable consistency.

A study by Özturk et al in Turkey was conducted to develop a patient privacy scale to identify whether nurses observe patient privacy in the workplace. The participants were 354 nurses working in hospitals. Data were collected through a questionnaire about the demographic characteristics of the nurses and their opinions about patient privacy. The CVI of the scale was 0.91 and Cronbach’s alpha was 0.93. The scale had five subscales. Although this scale is about patients’ privacy, it is directed towards an evaluation of nurses’ opinions about privacy and not towards patients (13). In a study in Iran, for the construction and validation of an instrument that investigates patient privacy, the researchers reviewed articles and books regarding privacy. The privacy component contained 41 questions relating to physical space (13 questions), information confidentiality (7 questions), and psychosocial aspects (21 questions). The CVI of items (or questions) ranged from 85 to 100%. Cronbach’s α coefficient for the privacy components of the questionnaire was 0.88. However, CVR, construct validity, and test–retest reliability coefficients were not indicated (7).

Limitations of the study

One of the limitations of the present study is that the deductive–inductive method was not used to extract items of the scale. There was also a low level of participation of the elderly. The perspectives of elders could have been analysed separately. Another limitation of the present study was the use of convenience sampling which does not allow for generalisation of the survey results to the population as a whole.

Conclusion

The findings show that the scale developed and validated in this study enjoys high validity and reliability and, thus, can be used to investigate patient privacy and secrecy in Iranian hospitals and medical centres. The use of the Iranian version of the Patient Privacy and Confidentiality Scale in educational curricula in medicine and allied health can familiarise university students with different aspects and components of patient privacy, secrecy, and confidentiality.

It is recommended that future studies use this questionnaire to measure the rate of observation of privacy in state and private hospitals.

Financial supportThis study is the result of a Master’s degree thesis and was supported by the Shahid Beheshti University, Tehran, Iran. No external funding sources were provided for this study.

Conflicts of interest None declared.

References

- Baillie L. Patient dignity in an acute hospital setting: A case study. Int J Nurs Studies 2009; 46: 23–3

- Raee Z, Abedi HA, Shariari M. Investigating the situation of respect for the privacy and dignity of patients by nurses in Isfahan hospitals. J Educ Ethics Nurs. 2015;3(2):13–22.

- Heidari M, Anooshe M, Azadarmaki T, Mohammadi E. The process of patient’s privacy: a grounded theory. J Shaheed Sadoughi Univ Med Sci.2011;19(5) 644-54.

- Calleja P, Forrest L. Improving patient privacy and confidentiality in one regional emergency department – A quality project. Australas Emerg Nurs J. 2011;14(4):251–6.

- Yura H,Walsh M. The nursing process. 5th ed. Norwalk, CT: Appleton & Lange. 1998.

- Tehrani TH, Maddah SSB, Fallahi-Khoshknab M, Shahboulaghi FM, Ebadi A. Perception of hospitalized patients regarding respect for privacy. 2018;13(1) 80-1.

- Nayeri ND, Aghajani M. Patients’ privacy and satisfaction in the emergency department: A descriptive analytical study. Nurs Ethics. 2010 Mar;17(2):167–77.

- Mohajjel Aghdam A, Hassankhani H, Zamanzadeh V, Khameneh S, Moghaddam S. Nurses’ performance on Iranian Nursing Code of Ethics from patients’ perspective. Iran J Nurs. 2013 Oct;26(84):1–11.

- Zirak M, Ghafourifard M, Aghajanloo A, Haririan. Respect for patient privacy in the teaching hospitals of Zanjan. Iranian J Med Ethics Hist Med. 2015;8(1):79–89.

- Ebrahimi H, Torabizadeh C, Mohammadi E, Valizadeh S. Patients’ perception of dignity in Iranian healthcare settings: A qualitative content analysis. J Med Ethics. 2012;38(12):723–8.

- Dehghani A, Karimipour F, Parviniyan AM, Khaki S, Shamsizadeh M, Beyramijam M. Enactment of professional ethics standards compliance in patients and nurses prospective. J Holist Nurs Midwifery. 2015;25(4):64–72.

- Hajbaghery MA, Chi SZ. Evaluation of elderly patients’ privacy and their satisfaction level of privacy in selected hospitals in Esfahan. Med Ethics J. 2015;8(29):97–120.

- Özturk H, Bahçecik N, Özçelik KS. The development of the patient privacy scale in nursing. Nurs Ethics. 2014 Nov;21(7):812–28.

- Chignell MH, Quan-Haase A, Gwizdka J, editors. The privacy attitudes questionnaire (paq): initial development and validation. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications; 2003.

- Foroozadeh M, Kiani M, Afshar L, Bazmi S. Children’s privacy in pediatric wards in teaching hospitals affiliated to Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences: 2014–2015. Arch Pediatr Infect Dis. 2016;5(1): e59868. Doi:10.5812/pedinfect.36539

- Dehghani F, Abbasinia M, Heidari A, Salehi MN, Firoozi F, Shakeri M. Patient’s view about the protection of privacy by healthcare practitioners in Shahid Beheshti Hospital, Qom, Iran. Iran J Nurs. 2016 Feb;28(98):58–66.

- Woogara J. Patients’ privacy of the person and human rights. Nurs Ethics. 2005 May;12(3):273–87.

- Williams B, Onsman A, Brown T. Exploratory factor analysis: A five-step guide for novices. Australas J Paramedicine. 2010;8(3):1–13.

- Polit DF, Beck CT. Essentials of nursing research. Philadelphia,Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009.

- Waltz CF, Strickland OL, Lenz ER. Measurement in nursing and health research. America, Springer; 2010.

- Ebadi A, Zarshenas L, Rakhshan M, Zareiyan A, Sharifnia S, Mojahedi MJTJ. Principles of scale development in health science. Iran, Jafari, 2017.

- World Health Organization. Process of Translation and Adaptation of Instruments; Geneva: WHO;2014 [cited 2020 May 25]. Available from: http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/research_tools/translation/en/

- Floyd FJ, Widaman KFJ. Factor analysis in the development and refinement of clinical assessment instruments. Psychological Assessment. 1995;7(3):286.

- Fischer KE. Decision-making in healthcare: A practical application of partial least square path modelling to coverage of newborn screening programmes. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making. 2012;12(1):83.

- Antony MM, Barlow DH. Handbook of assessment and treatment planning for psychological disorders. Pennsylvania, Guilford Press; 2011.

- Hosseini M, Borhani F, Maleki M, Ahmadi F, Zohari S. Relationship between perceived social support and autonomy and participation among patients with spinal cord injuries. Res J Med Sci. 2016;10(4):399–405.

- Torabi M, Borhani F, Abbaszadeh A, Atashzadeh-Shoorideh F. Ethical decision-making based on field assessment: The experiences of prehospital personnel. Nurs Ethics. 2019 Jun;26(4):1075–86.

- Borhani F, Abbaszadeh A, Moosavi S. Status of human dignity of adult patients admitted to hospitals of Tehran. J Med Ethics Hist Med. 2014;7:20.

- Mehdipour-Rabori R, Abbaszadeh A, Borhani F. Human dignity of patients with cardiovascular disease admitted to hospitals of Kerman, Iran, in 2015. J Med Ethics Hist Med. 2016;9:8.

- Sharifi S, Borhani F, Abbaszadeh A. Factors affecting dignity of patients with multiple sclerosis. Scand J Caring Sci. 2016 Dec;30(4):731–40.doi: 10.1111/scs.12299.

- Borhani F, Abbaszadeh A, Rabori RM. Facilitators and threats to the patient dignity in hospitalized patients with heart diseases: A qualitative study. Int J Community Based Nurs Midwifery. 2016 Jan;4(1):36–46.

- Boozaripour M, Abbaszadeh A, Shahriari M, Hashiani AA, Borhani F. Care: The first priority of professional values from the perspective of Iranian. Ann Trop Med Public Health. 2017;10(3):678–83.

- Soleimani F, Anbohi SZ, Esmaeili R, Pourhoseingholi MA, Borhani F. Person-centered nursing to improve treatment regimen adherence in patients with myocardial infarction. J Clin Diag Res. 2018;12(1):1–4.

- Farokhzadian J, Nayeri ND, Borhani F. The long way ahead to achieve an effective patient safety culture: Challenges perceived by nurses. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018 Aug 22;18(1): 654.Doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3467-1.

- Kazerooni K, Pazokian M, Nasiri M, Borhani FJRLdH. Expectations and satisfaction of elderly people with health services provided at a public nursing home in Iran. Rev Latinoam Hiperte. 2019;14(1):95–101.

- Zihaghi M, Saber S, Nouhi E, Kianian T. Respect for privacy by nurses from the perspective of the elderly hospitalized in internal and surgical wards. Med Surg Nurs J. 2016;5(3):27–33.

- Daly J, Elliott D, Chang E, Usher E. Research in nursing: Concepts and processes. In: Daly J, Speedy S, Jackson D, editors. Contexts of nursing: an introduction. Chatswood, Australia: Elsevier; 2014:137–56.

- Ahmadizadeh MJ, Ebadi A, Sirati Nir M, Tavallaii A, Sharif Nia H, Lotfi AS. Development and psychometric evaluation of the treatment adherence questionnaire for patients with combat post-traumatic stress disorder. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2019 Mar 22;13:419–30.

- Koo TK, Li MYJ. A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. J Chiropr Med. 2016 Jun;15(2):155–63.